Carnival. Chaos. Clarity - Carneval in CCAA

A return to Cologne Carnival—once loathed, now seen with new eyes. A story of shifting perspectives, wild costumes, and self-discovery.

A few days ago, I visited a place I never thought I would dare to return to, Kölner Karneval, or the Cologne Carnival.

A Childhood Love for Karneval

As a child, I lived in Cologne for a few years. CCAA. Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium, this is how the romans would call it, who once occupied the city. Cologne has an interesting roman history. But today we turn to the days of a festival originated in the pegan traditions, which then were tolerated by the christian church as a celebration before the fasting period of Lent, where people could eat and drink before starting their fast.

In my childhood years, I loved Carnival. Everyone dressed up, and on Sunday and Monday, the grand parades "Rosenmontagszug" marched through the streets. The decorated floats carried oversized sculptures—adults recognized the political satire in them, while children were simply fascinated by the gigantic figures.

It rained. But not water. Candy fell from the sky! From every float, chocolate, sweets, and flowers were thrown into the cheering crowd.

On Tuesday, the last day of Carnival, the "Nubbel"—a straw doll, a sort of scarecrow—is publicly burned as the bearer of all sins. Since the 20th century, pub owners in Cologne have hung the Nubbel above their doors or inside their bars. On Veilchendienstag (Shrove Tuesday), amid great spectacle and a funeral procession, the Nubbel is set on fire while the crowd chants:"Who is to blame?" – "The Nubbel is to blame!"

People jump over the burning figure, symbolically shedding their sins—sins accumulated over the past year, especially in the days leading up to the burning. This Nubbel burning ritual is a macabre tradition rooted in medieval scapegoat rituals, where a puppet or figure was sacrificed as a stand-in for the misdeeds of the community.

After the parades, children return home with seven bags full of sweets. The first thing they do? Dump everything on the floor and start sorting—chocolates, chewing gum, popcorn candy, lollipops. Anything they don’t like is traded with others.

From Festive Joy to Teenage Rejection

As a teenager, I began to despise the festival. While children drowned in a sugar rush, teenagers and adults drank themselves into oblivion. This blind, excessive alcohol consumption repulsed me.

Drinking is a big part of Carnival traditions in Germany, yet I found it unbearable. Nothing more than a socially sanctioned mass escape from one's own stiffness. For the other 360 days of the year, people walked around as if they had a stick up their butt. But then, the moment they tied a colorful bow tie around their neck and reached a dangerous blood alcohol level by 9 a.m., suddenly, everything seemed allowed.

The opposite sex was approached without hesitation, as if the first sip of Kölsch had washed away their social awkwardness along with it. And this newfound uninhibitedness didn’t stop at words—it carried over to physical behavior. Boundaries blurred, hands landed where they didn’t belong, and the city turned into one giant Sodom and Gomorrah.

It felt like a lie—as if, for a few days, everyone dared to be someone they would never have the courage to be otherwise.

Revisiting the Madness: A New Perspective

This time though, I watched the scene around me—and I enjoyed it. Not the alcohol consumption—that’s still not my thing, though on this day, I simply accepted it.

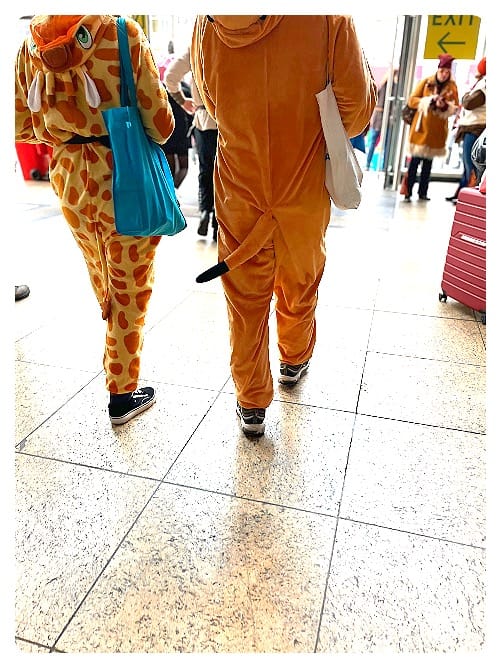

On my way there, I wasn’t sure how much I should dress up. So, I grabbed a polka dot skirt I hadn’t worn in ages, put on a pair of Minnie Mouse ears, and cautiously eased my way into the Carnival spirit. But the moment I stepped outside, a tiger walked past me. Everywhere I looked, people were dressed in elaborate, carefully chosen costumes.

In my memory, Carnival days had always been gray and rainy. Sad clown costumes dragging the filth of the streets behind them. But today, the sun was shining. There was a lightness in the air, an effortless joy.

Everyone was dressed up. Even the window cleaners wore wigs.

I spent the day at a party at Gaffel Kölsch. The scene there reminded me a little of Berghain. Loud music blasted from the speakers, forcing people to scream at one another. Kölsch flowed in streams, effortlessly making its way down thirsty throats. The creativity in Karneval costumes amazed me, for hours I was just watching the people around me—it felt like a wild fashion show.

But instead of Gucci and Prada, fries and ketchup walked past me. Miss Universe floated through the room in a long blue dress adorned with tiny planets. Elton and Elvis were guests. And all of it was accepted as absolute normality.

When I finally stepped out of this bubbling mass of party energy and onto the street, I felt as if I had danced through an entire night—that surreal moment when, after hours of wild, dreamlike chaos, you suddenly realize that a new day has begun and the sun is already rising. It felt unreal. Berghain vibes, but in color.

It was 3 p.m. as I walked through the train station, past the first casualties of alcohol. But this time, I smiled to myself.

For anyone experiencing Cologne Carnival for the first time, this is a true deep dive into Germany's festival culture.

What did I learn that day at the Carneval in Cologne?

That things are often nothing more than what we make of them. Carnival had been the same as every year, for decades, for centuries. But I was different. And because I saw it through different eyes, it felt different.

What I had once rejected as a teenager, what had annoyed me, what I had run away from—today, it filled me with gratitude, love, and a deep affection for these people. People who celebrate their city, their friends, their creativity, and themselves. People who, for a moment, step out of their everyday lives and embrace the freedom of the moment.

Things are the way we choose to see them. And that choice is ours alone—to decide how we want to feel.

Be Well,

Vaselisa